"I don't battle anymore! I uplift motherfuckers!" - GZA

Sunday, March 19, 2006,4:41 PM

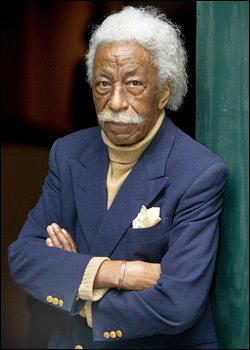

Gordon Parks 1912-2006

by Greg Tate

Talk about flipping the script: Gordon Parks was born dead and damn near buried alive. Then went on to live to the ripe young age of 93. Fortunately, two doctors were attendant that November 30 in 1912. The thinking one had the brainstorm of immersing the stillborn infant in ice water to jump-start his heart and gave him a fully operational third eye in the process. Total immersion of head and heart would become his lifelong m.o. Given his staggering output as photographer, filmmaker, writer, painter, choreographer, and composer, he seems to have not slept much after his rebirth. Orphaned by his mother's death and sent to live with an aunt, he was thrown out into a subzero Minnesota winter at 14 by her model-of-man's-inhumanity husband. So take a memo: the mark of a visionary is being a young Black man in the Depression and blowing $7.50—a month of meals back then—on a camera. Only lo and behold the fledgling shutterbug begins showing at the local Eastman Kodak shop by impressing the manager's wife.

As with Oscar Wilde and Duke Ellington, Parks's greatest invention was himself. Here we have one of those impossibly rare instances where the work and the man measure up as parallel monuments. Carlos Castaneda's Don Juan decrees that "a warrior must be impeccable," and Parks—dapper, debonair, perpetually down for the cause, and ready like a samurai for whatever the funk called for—epitomized that edict. But what of the work? In his books you'll find immaculate, inventive, indelible images of society, high and lower than low. Other than Richard Avedon, it's hard to think of another native-born photographer who so gracefully moved between haute couture and the street. When aimed at an injustice, Parks's camera could pull you so close to the pathos that you might overlook his skill and surface beauty. After just one day in 1930s Washington, D.C., encountering what he called the worst racism of his life, he shot his first classic, American Gothic, in which office cleaner Ella Woods grips a broom in one hand and a mop in the other in the pose of Grant Wood's stoic farm couple while the red-white-and-blue hangs in the background like a shroud. Woods, Parks reported, cleaned the office of a white woman of no more education who'd also started at the company with a mop. Parks's boss thought the photo would get them all fired for its implicit critique of the America way. Much to his chagrin it turned up weeks later in The Washington Post.

This wasn't the last time the gatekeepers found his work too Black too strong. A series he shot of Black fighter pilots training during WWII was held back by a military unready to present that image of the Black soldier. His Life series on poverty in Brazil's favelas was initially reduced to one shot by his editors, who thought Parks's countrymen didn't want to know what poverty looked like in carnival Rio. Parks nearly resigned until fate had The New York Times run a story the next day on the U.S.'s obligations to Brazil's oppressed. The series generated donations of $30,000; its asthmatic subject spent two years in the U.S. being cured pro bono and bought his family a new house. Parks's immersion process would also produce portraits of a family who shared their Chicago project apartment with him. These photos too earned their subjects a house, but the father would die after coming home drunk and setting it ablaze and eventually nearly all the children would perish in jail or of AIDS.

Parks often found himself on the other side of the camera sharing the most intimate and tragic details of his subjects' lives. He once took a ride tailed by the cops with some young L.A. Panthers with guns in their laps. One asked him if he would still choose the camera over the gun, as he'd declared in his 1967 memoir, A Choice of Weapons. Parks reiterated his belief. Two weeks later the Panther was dead. When Life nearly betrayed the trust he'd gained from a young Chicago gang leader by choosing a cover shot of the youth with a smoking gun, Parks destroyed the negative. In 1963, Life asked him to "infiltrate" the Nation of Islam. Instead he and Malcolm X became quick friends. Parks is the godfather of Malcolm's daughter, Qubilah, and is cited in The Autobiography as a successful Black man who never lost touch with his people.

Because Parks transitioned into filmmaking just as TV was destroying photojournalism, the post-1970 generation knows him primarily as the aristocratic white-haired eminence who directed Shaft. And while Parks's autobiographical cinematic debut, The Learning Tree, is in the National Film Registry, his most critically acclaimed films, The Super Cops and Leadbelly, have languished unavailable for far too long. One online pundit thinks the mostly white Super Cops has aged far better than The French Connection and The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, while Roger Ebert calls Leadbelly hands down the best movie about a musician ever. I'd go further and say Leadbelly is the most lyrical work save August Wilson's about the roustabout world of violence, bloodhounds, swamps, railcars, bordellos, juke joints, cotton fields, and chain gangs that spawned the blues and its alchemical admixture of sardonic joy and short-lived sensual pleasure. Parks nearly abandoned Hollywood the day he found out Paramount had opened it in a New York porno theatre. It defies two of Hollywood's still standing prohibitions by depicting Black people enjoying themselves sexually and Black men defending themselves against bloodthirsty crackers. No wonder it remains unavailable on VHS or DVD. You can see Leadbelly was where Parks took all he knew about the blues as musician, lover, rambler, and Depression survivor, and translated it into gritty impressionist cinema—earthy, erotic, dust-filled.

No one who knows all this about Parks would be surprised to find that even in his late eighties he was experimenting with computer-generated imagery and finishing his last book, the just published A Hungry Heart. The comedian Franklyn Ajaye has a routine that ends, "They don't make 'em like that anymore. They never did.'' When they come as self-made as Parks, that tells the tale.